It occurred to me that beneath the surface of the

mundane in life exists our mythical realm, the place

where dreams come from, or where we find solace in

times of meditation or contentment. When riding in

the car on long trips as a child, I would stare

trance-like for hours on end as landscapes and

buildings whizzed by, transformed by the movement of

the car into new shapes and colors. The speed

created blur, the magical tool that put the world in

flux. No wonder, then, that I became fascinated

with the odd images produced at the beginning of a

film roll, and sometimes the end, by winding the

film into place or winding it to end the roll.

Shots were taken, images captured without knowing,

and the motion of winding often shook the camera

enough to cause common problems for images: blurry

captures and unexpected blurred “panning” shots.

I was captivated by the melded colors, the odd

formations that were these “bad slides.” Mostly

those film images went into the trash immediately,

but occasionally stunning “pictures” emerged which

made me dreamy with wonder. Back in the film days,

it was practically unthinkable to waste film, to

just shoot rolls and rolls experimenting. Always

there was a need to be careful in the use of film,

as each roll first cost to buy then, of course, to

process. The cost encouraged technical expertise

and a “never miss a shot” ethic, other than to

bracket exposures from which to select a preferred

exposure.

Early Experiments with Motion

When the digital SLR (single lens reflex camera)

became affordable (for me it was the Canon 10D) the

idea of film and economy went right out the window

immediately. The film was prepaid and so was the

processing. No lab costs. This meant suddenly all

constraints of cost were now gone and the idea of

experimentation was immediate. Shoot, shoot without

a care. The images could be quickly and easily

deleted, and also could be burned to CDs if there

wasn’t enough hard drive space for storage. The

image could be instantaneously processed in

Photoshop and printed with results that rivaled

anything available from the lab. The workflow became

individuated. Photographer and processing lab

became one and the photographer became autonomous.

Experimenting with panning shots, where a moving

object such as a car is shot to be in focus while

the background becomes a blur of lines connoting

speed, became an obsession for me. Certain images

emerged which embodied the best results of this

technique such as “The Light Walkers” (I Hear

Music, Step into the Light, and Walk

Like an Egyptian). Captured in Vancouver during

a vacation trip, the figures move amongst richly

saturated backgrounds replete with motion and

color. The point of these photos is that they

launch the figure and us into a mythic realm, a

place that exists only perhaps to other creatures

imbued with special abilities, as dogs are endowed

with a sense of smell ten times beyond our

capabilities. When I began to capture these panning

shots consistently, it occurred to me that while

these images didn’t really exist in life yet were

here in front of me on paper or monitor, perhaps the

image signified another realm which exists beyond

our normal day-to-day perceptions but lies just out

of reach. Considering current string theory,

perhaps this notion is not so far fetched.

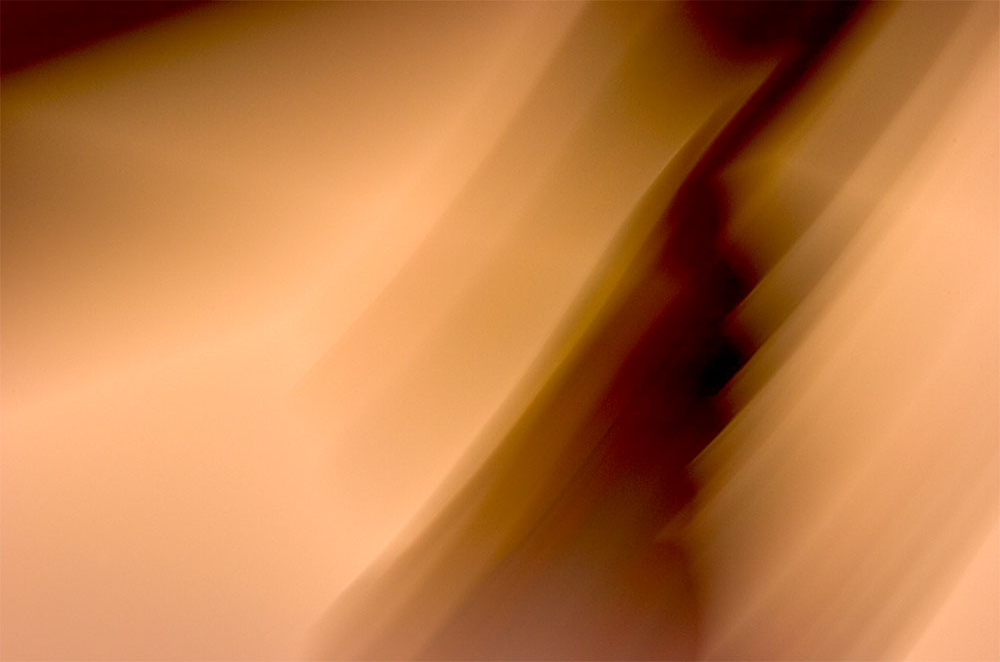

Step

Into The Light

Step

Into The Light

Foreground

Subject/Background Subject Photography

I began experimenting with reversing the technique

of panning a moving object, instead panning the

background itself while still focusing on the

object. I see this decision as akin to Brancusi’s

recognition of the base as equally as important as

the sculpture. This thinking began forming the

basis for what I now think of as “foreground

subject/background subject” photography. Placing an

equal emphasis on both aspects shattered traditional

confines for me.

Just as I had built jigs and machines to accomplish

certain processes in woodturning and sculpture, I

began experimenting with ways to control motion

through prescribed paths, using linear motion

rails. Moving Money was an early experiment

that allowed the blur of the stationary object to

become prominent as a design element in the finished

photo itself. The coin was still and the camera

itself moved along a course I had predetermined.

Shooting hundreds of images, I varied the motion,

the path, the blur, through bracketing and focusing,

until eventually one image emerged that captured the

essence of what I was shooting for. It was like

Jacob wrestling with the angel--after days and days

of struggling, finally the process gave up the

sought after prize.

The photograph seemed to me to reveal the unseeable

effects of light and motion that modern physics

explains through theories and formulas. I settled

for the results of the experiment alone, not needing

to understand how the universe actually works. To

have a part of it, a meager scrap would do. The

mystery of light and the transformation of objects

were illustrated to me by the process I had worked

out.

Moving Money

Armed with new knowledge and understanding about how

the effects of light and motion allow a glimpse into

the hidden realm, I began applying the technique to

photography of objects in nature, exploring form and

natural light. The first resulting image that

transcended the ordinary, visible world and entered

into the real but unseen world was Slit-Screen.

It was shot outdoors using an object of no

consequence to transform the components of the here

and now into the here but unseen.

The breakthrough had occurred earlier, actually,

when while shooting a dog toy as a still life, I

began playing with the motion techniques. The forms

and colors of Dog Toy create a “normal” image

that I appreciate as it is.

Dog Toy

But as I applied my motion technique, forms which

seemed like gifts from the machine (camera) began to

emerge, not quite perfect in terms of exposure, but

rather, an ideal example of the hoped for process of

shooting. With this breakthrough came the quest to

conquer or master the process, that I am to this day

still obsessed with. Early examples from this time

follow: Socked In, Icebergs Collide,

Sand Storm.

Socked In

Icebergs Collide

Sandstorm

Although “noisy” (a term referring to digital

interference in current DSLR technology) the images

confirmed the potential of the process. As I

applied the technique to simple objects, one truth

became evident: the process could be used on

anything and could unlock the hidden world which

lies beyond the evident to yield the unperceived.

This process, while always possible, was and still

is extremely difficult and unstable. I think of my

yield, the number of useable images per number of

shots taken, as a ratio determined by the

craftsmanship and vision applied to any given

session. As a craftsman, I understand the

determination and discipline required to master

technique. To turn wood with mastery involves years

of disciplined practice. To do this kind of

photography requires the same commitment to time and

practice.

The

Technique

These early experiments lead to months of

practicing, attempting to master the techniques to

increase the yield. Slit-Screen emerged like

a strange visitor from another planet. In my view

it was glorious, an accomplishment that was an

example of this technique and an image which held

its own in the tradition of the abstract photography

of Edward Weston, et al, where an image taken out of

the context of the realm of daily life became

celebrated, perhaps, at least for me, achieving an

iconic state.

In Slit-Screen, the process, unwieldy and

unstable as it was gave up an early image that began

to fulfill the self-imposed requirements which form

the confines within which I currently work. It is

when the image becomes something that was never

there, but is instead transformed by the process,

that it makes a new essence based on light and

motion. It is a task of pulling light with the

camera, or perhaps pushing it, maybe coaxing it

along. It turns out that it must be a highly

technical process to achieve consistency or to go

beyond mediocrity or cliché, but the results are a

kind of drawing with the camera where the tool

becomes a stylus of sorts and the photograph becomes

more like a painting.

Slit-Screen

Gradually, it became clear to me that the camera

movement required to achieve consistent results was

not unlike the movements I employ as a woodworker,

woodturner, and sculptor. In woodturning, the

material moves (in fact it is all about movement)

and the tool is carefully manipulated through

various angles and pressures against the spinning

material. Slight repetitive motions, applying

subtle pressures, accomplish complex forms

translating to smooth surfaces and curves in the

material. Working wood often involves deft

manipulation of a tool such as a plane or a chisel

as it carves into the material held stationary in a

device such as a bench or vise.

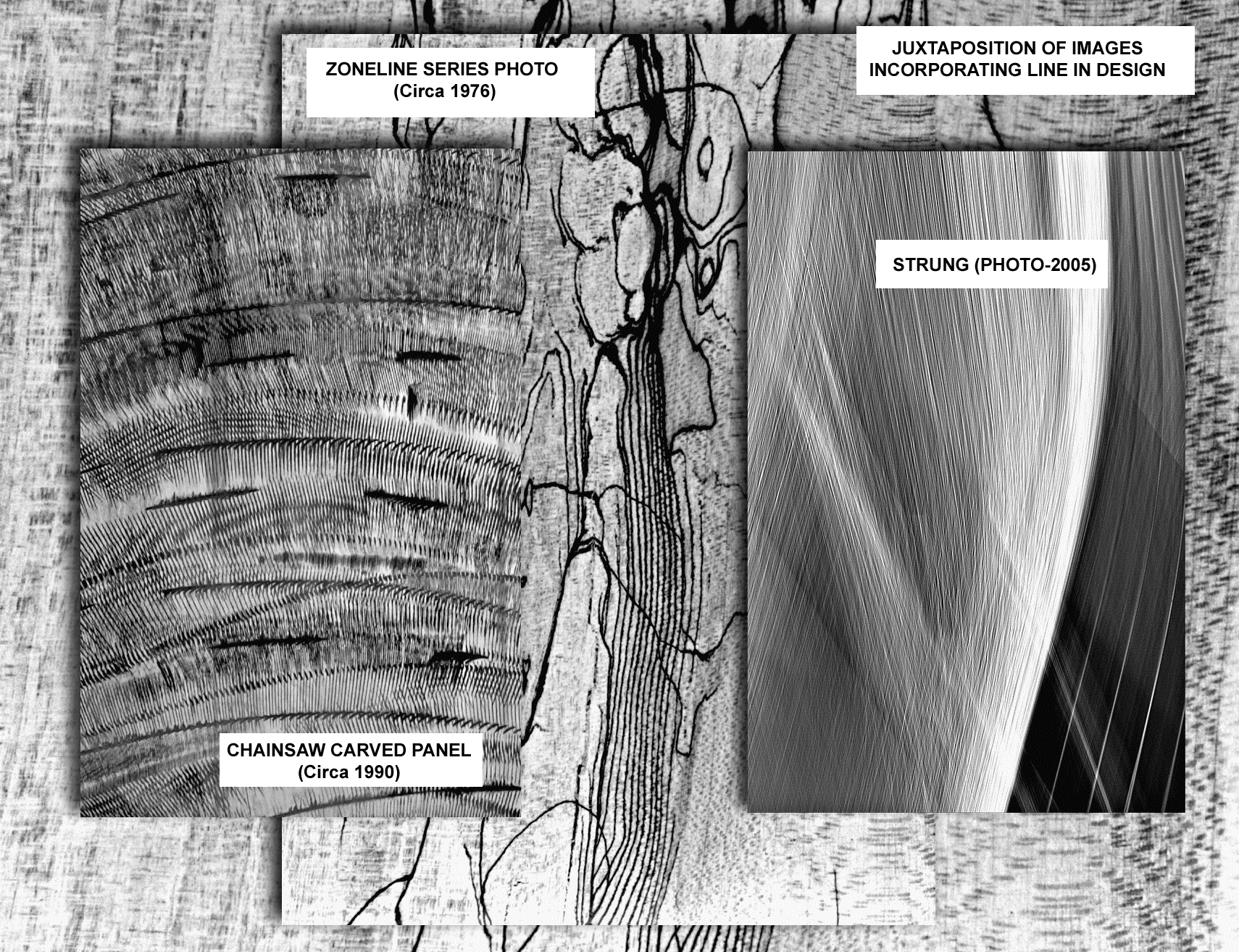

But perhaps the most direct relationship is the

similarity of the use of the chainsaw in carving to

the use of the camera in this kind of photography.

Subtle motions emanating from the wrist yield

profound results at the tip of the tool. When I

worked on my chainsaw carved panels I endeavored to

create a new vocabulary reflecting the nature of the

tool. The cuts and crosscuts became extremely

precise while simultaneously expressive. It was the

line in motion though an imposed curve which

fascinated me. So I began to look for this aspect

in my “drawing” with the camera. I view the current

work as a translation of these studied techniques, a

craft involving the highest degree of hand/eye

coordination.

Mark Lindquist woodturning at the lathe, circa 1979,

Henniker, NH studio

Perhaps it is the essential aspect of rhythm

absorbed from my early training as a percussionist

that has formed the basis of my work. The motion of

the wrist, the control of the hand, guided by the

eye, enables the personal expression which emerges

throughout my development as an artist. Inevitably,

the craft which is imposed upon the process lies in

service to my vision. I employ the tools to that

end and view them as an integral part of the

process. Just as the lathe became for me an easel,

the means with which to hold the work, so too now

does the camera become that extension of my hand

that allows me to shape and carve light.

The interplay of positive and negative space is

sublimated through the aspects of motion and

stillness. Specular light dragged like the tool

steel of the spinning chainsaw tooth creates line

and defines form. Color is the palette of natural

light. The division of time into fractions of

seconds reveals the colors and enables the shaping

of light-form, while the focusing of the aperture

determines the quantity of colors and sharpness of

line. Coupling these basic aspects together, the

precisely controlled motion of the camera, the

correct reading of the light, the careful

synchronization of the elements, occasionally the

gift from this process is realized.

Selecting and Printing the Image

It is the referral to painting, drawing, and

sculpture in art historical association that enables

me to find the images amongst a wasteland of

exposures. Wading through countless captures, the

right one reveals itself through conscious

observation. That one lone image becomes separated

from the rest, which are the packing of this one

prize. I shoot and reshoot until I capture the

image in-camera, as did traditionalist modernist

photographers who sought to make perfect negatives,

requiring little editing, cropping or exposure

adjustment. One of my goals is to work within these

confines, applying sound photographic principles to

my work flow. This quest for purity of image in the

traditional photographic sense validates the printed

object for me as uniquely photographic, although the

final result blurs the lines between many graphic

disciplines.

For me, photography has come of age—it is no longer

“about photography”—it has become a tool that

enables me to explore light, motion, and form.

While wrestling with the process to achieve my

desired outcome, I find this is not unlike any other

approach to making art. It is seeing and testing

within a climate of belief and doubt, where light

and shadow occasionally dance together but mostly

are at odds with each other. When late afternoon

light, personal energy and enthusiasm, sleight of

hand, and high technology meet, the stage is set for

the serendipitous occurrence. Then sifting through

the hay to find the needle begins. Eventually I look

to see many needles and little hay. That requires a

life long commitment.

I set out to obey photographic rules of proper

exposure and to process the images using the most

advanced post-processing techniques in Photoshop

(the digital darkroom as it is often called) and in

the most suitable manner, using the best fine art

papers and inks which have the greatest archival

longevity. Keeping the colors in gamut proves to be

the most challenging aspect of using the most

favored fine art papers.

I began printing Slit-Screen on Epson Velvet

Fine Art paper using the Epson 2200 Ink Jet Printer

with Ultrachrome inks as it was the most affordable

printer on the market capable of producing archival

quality prints up to a size of 13” x 19”. Gradually

getting a handle on the digital darkroom workflow I

began to achieve museum quality prints which now are

the state-of-my-art for the current images.

Eventually, larger prints will become possible, as

the images from my cameras (the Nikon D2H and D2X)

can yield spectacular results at up-scaled sizes

that are appropriate. The aspect of post-processing

the images through carefully managed color workflow

is a tricky business.

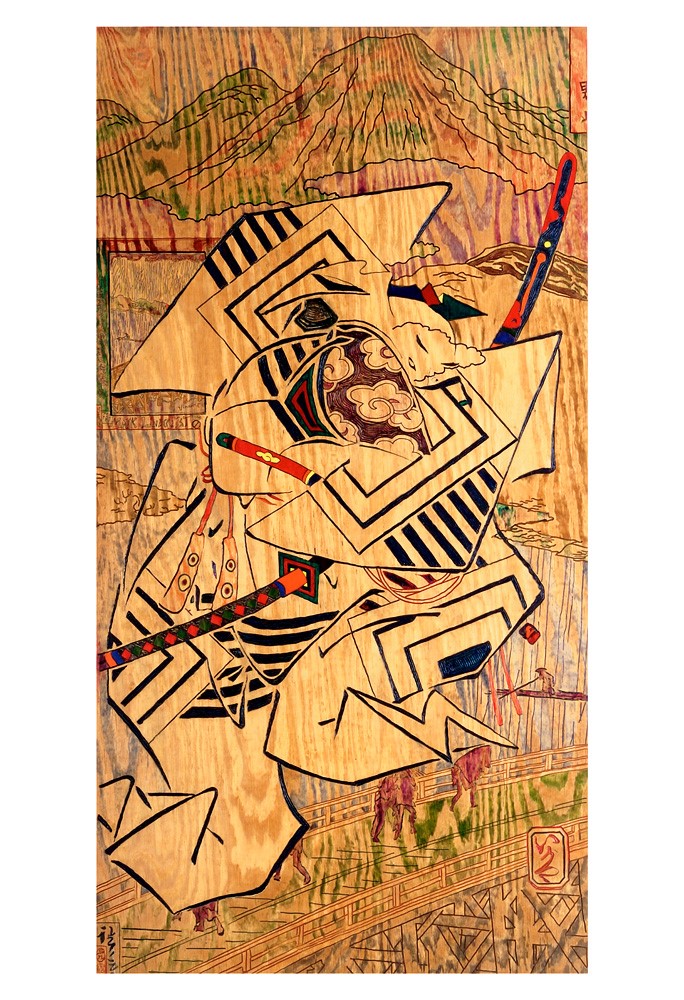

Reflections on Chainsaw Carved Polychromed Plywood

Works

When I began creating chainsaw carved panels on

wood, I used techniques that came directly from the

world of woodworking but were modified to enable my

own avenues of expression. While swinging the

chainsaw across the surfaces, skating the blade, a

quick kind of drawing was accomplished, like

sprezzatura, a technique that embodies the essence

of the artist’s vision in a quick sketch. The

process required highly sophisticated techniques,

mastery of process, and purpose of vision.

“Wetland Series (De-Compositions)” - 1990s

Photo: John McFadden / Lindquist Studios

In my “Stratigraph” and “De-Composition” pieces, I

referred to the work of the Abstract Expressionists

and began developing a vocabulary and vision of “a

modernist approach to postmodernism.” The objects

vacillate between tenets of high modernism and the

ambiguities of postmodernism, exploring the realms

of slipping signifiers and pastiche.

So too are my photographs explorations of modernist

goals and postmodernist commentaries regarding form,

painting, light, and expressionism. I refer, often,

to the approaches of period painters such as

Malevitch, making tongue-in-cheek references in the

titles of my photographs. (While the titles refer

to earlier artists and historical movements, there

are purposely no direct similarities between

images.)

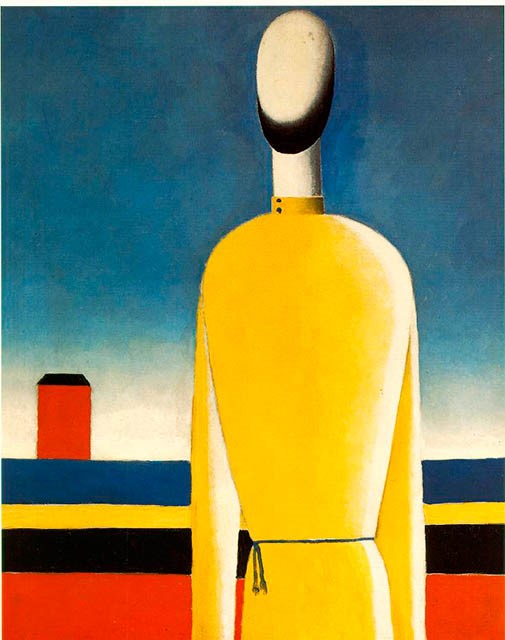

Complex Presentiment: Quarter Figure Wearing a

Tangerine and Orange Shirt (left)

Kasimir Malevitch Painting (right)

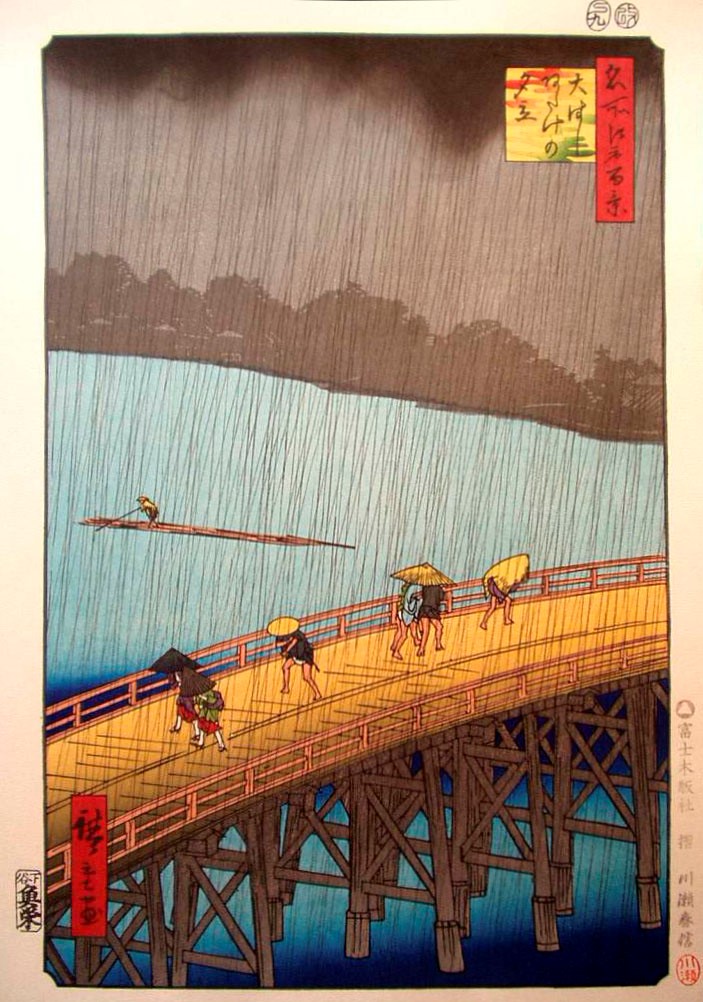

The Influence of Ukiyo-e Prints

While studying Japanese art history with Dr.

Penelope Mason in the late 80’s through early

nineties, I began a detailed enquiry into the design

principles of Ukiyo-e woodblock prints,

incorporating into my work such emotive concepts as

the steeper the angle the greater the drama within a

scene. Often Ukiyo-e images were tightly cropped,

producing a feeling of floating. The name Ukiyo-e

means just that: “the floating world.” I also

studied the influence of the design principles of

Ukiyo-e on the work of European painters of the 19th

century.

Just as van Gogh referred to Hiroshige’s famous

woodblock print Sudden Shower at Ohashi

(left) in his painting Japanaserie: Bridge in the

Rain, (right) I refer to van Gogh’s reference in

a carved and polychromed panel called “Sudden Reign”

(referring to the state of war), creating layers of

meaning. The pseudo-seal or chop mark on the left

is a graphic reference to van Gogh’s actual redux

painting of the woodblock print. The carved panel

is neither painting nor print but rather woodblock

itself reversing theindexicality of the process of

making a series of Ukiyo-e prints. I rearrange the

significations of the elements of the original

prints; whereas the figures in the prints by

Hiroshige are running, covering themselves from

ordinary rain, my figures are covering themselves as

they run from the rain/reign of terror, indicated by

the over-arching cloud-like figure which symbolizes

nuclear war, or terror coming from the sky. Using

the “copy” of van Gogh’s copy of a copy (referring

to the fact that prints are copies of an original)

as a stamp, means I call upon van Gogh’s act of

appropriation as a “seal of approval”—if it was okay

and good enough for van Gogh to appropriate and

refer to the image, then it is likewise okay for

me.

SUDDEN REIGN (Mark Lindquist 1990)

Photo: John McFadden / Lindquist Studios

Recently a sculpture of mine from that period has

been acquired by the Smithsonian Museum:

Mark Lindquist, Akikonomu

(Ichiboku Series), 1989, cherry and polychrome

Evolution of My

Photography

I am pleased to be coming back to photography in a

concentrated form at this point in the development

of my work. I began photographing seriously while

studying art in college in the late 1960s. Later,

my wife Kathy and I studied photography and fine art

black and white printing with Ron Rosenstock, who

had worked with Minor White at MIT. Kathy and I

shared a studio and darkroom in New Hampshire. She

became a free-lance magazine photographer, while my

interests were in pursuing photography as a form of

artistic expression in itself, as well as in

producing a record of my other artistic endeavors.

For over thirty-five years, I have practiced art

documentation photography, working professionally

for other artists and art institutions as well as

for myself.

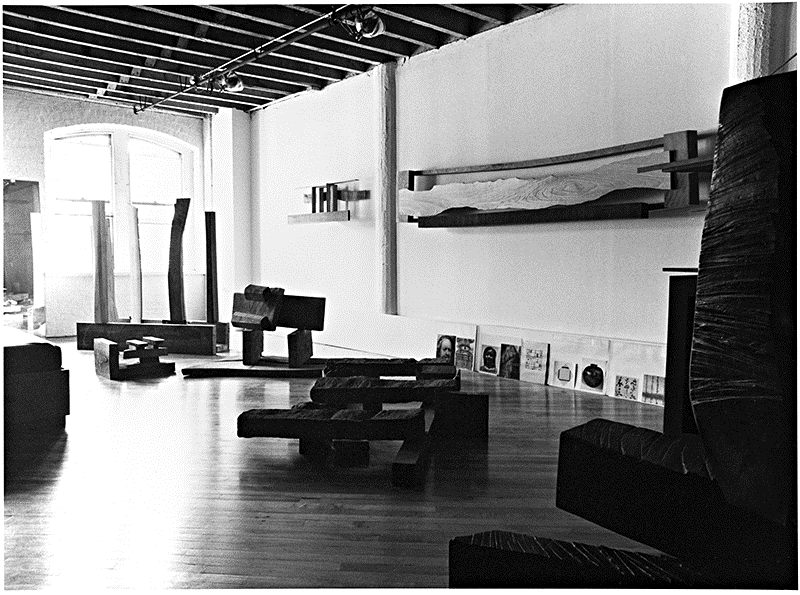

Will Horwitt’s NYC Studio

photographed by Mark Lindquist, circa1980

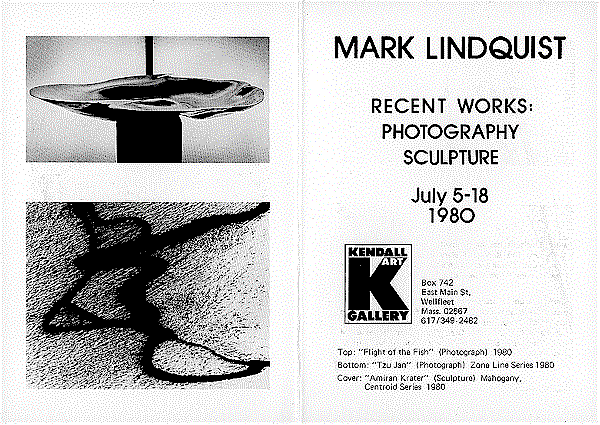

My early purely photographic works were in black and

white shot with a Mamiya M645 or an Arca Swiss 4 x 5

camera and processed in our darkroom, using a cold

light and Zone VI and other fine art papers. This

exploration of the black and white print culminated

in the late 1970s in the “Zone Line Series,” which

are 10” x 14” prints made from 4” x 5” negatives of

the surface of pieces of spalted wood less than two

inches square. The images transcended their

identity as wood, taking on the appearance of

Japanese brushwork, a theme that runs through my

work in all media. A one-person show of the Zone

Line Series photographs was held at the Kendall

Gallery in Wellfleet, Massachusetts, in 1980.

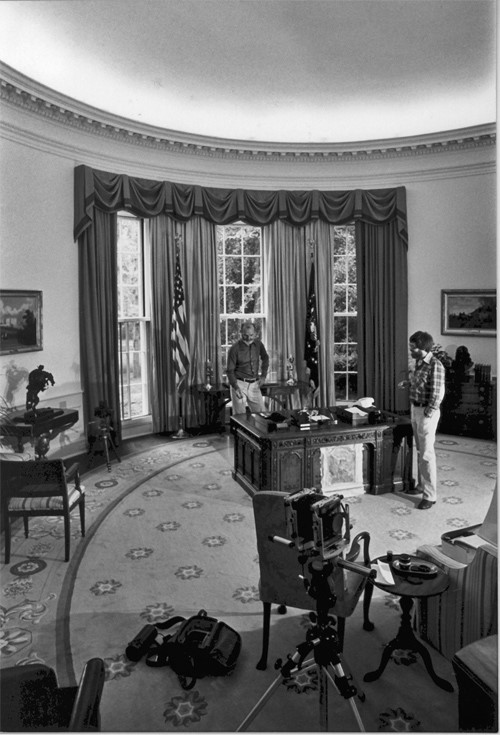

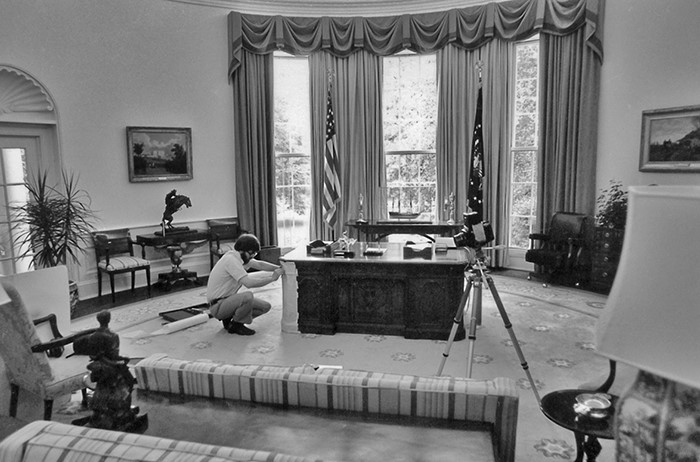

I have also used photography as a tool for

documenting craftsmanship and technique. In 1977, I

assisted Robert Whitley in the reproduction of the

presidential desk for the JFK Memorial Library,

photographing and patterning the original desk in

the Oval Office.

I worked with professional photographer Bill Byers

to produce the technical photographic series in my

book, Sculpting Wood, published in 1986. In

1992, I reproduced and photographed ancient clay

working techniques for a scholarly work on Japanese

art, written by Dr. Penelope Mason.

In 1996, I began using digital technology, using

the Polaroid PDC 2000 professional camera and

Photoshop version 4 as an image-editing tool. In

2004 I began photographing with the Canon 10D

Digital SLR, then moved to the Nikon D2H and D2X

professional systems, and have all but abandoned

film in favor of digital media.

The

Common Thread

A common thread throughout my work, no matter the

medium, the subject, or the technique, is the

presence of naturally occurring line. Since my

childhood days of working with my father, harvesting

and turning spalted wood (partially decomposed wood

marked with rich dark zone lines formed by

carbonaceous deposits), the use of natural line

reasserts itself continually in my work. I have a

trust in the natural formations and graphic patterns

that exist everywhere, believing that these natural

occurrences are the foundation of graphic art since

the beginning of mankind. Pattern and imagery, like

spalting or the cracking that occurs in wood, are

all around us both in this world and the unseen

world. Just as airflow patterns are viewed in

laboratory wind tunnels by adding smoke, to me the

camera and my process expose the unseen patterns

occurring in nature. In many ways this is like

cutting the log to expose the grain and, when

present, the naturally drawn lines of spalted wood.

The photos in this portfolio are printed on Epson

Enhanced Matte paper. I use(d) Epson Ultrachrome

inks in an Epson 2200 color printer. These

photo-abstract images are all in-camera photographs,

not manipulated or added to after the image has been

captured by the camera. I use(d) the Nikon D2H and

D2X cameras and process(ed) the photos with a

carefully managed color workflow on an Apple G5 Dual

2 Ghz Machine with 6 GB Ram. The works represent 2

years of endeavor with this process, after a

lifetime of study.

Mark Lindquist

December, 2005 Lindquist Studios | Quincy,

Florida